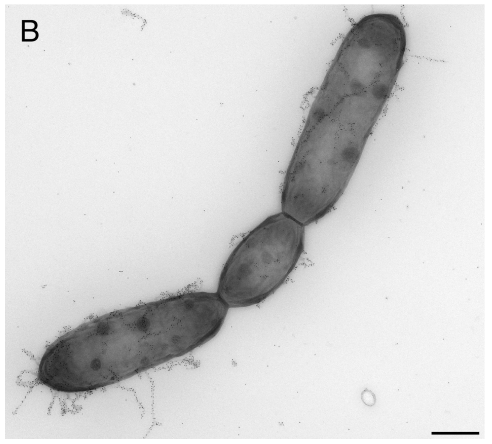

Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG (ATCC 53103, also known as LGG), is a strain of L. rhamnosus and is one of the most well-known probiotics strains. It was isolated in 1983 from the intestinal tract of a healthy human being by Barry R. Goldin and Sherwood L. Gorbach1.

LGG has several features that distinguish it from other probiotics strains; First, LGG is highly acid-resistant, which gives it the ability to survive the acids and bile of the human stomach and intestine3. Furthermore, LGG strains could adhere to mucosal structure and colonize the intestine4, and exclude or reduce pathogenic adherence in a way to produce compounds antagonistic to pathogen growth5. All these properties make LGG a particularly remarkable probiotic strain.

These characteristics have led to extensive research on the prevention and treatment of various diseases that eventually caused the strain to become known as the world’s most-studied bacteria. The first commercial use of probiotics with LGG was launched in Finland in 1990 under the Valio Gefilus® brand. Currently, LGG is the most representative probiotic strain of Chr. Hansen.

How was the safety of LGG evaluated? As the popularity of LGG increased followed by its consumption, the possibility of side effects caused by the bacterial infection increased. However, this Lactobacillus bacteremia issue that can be induced from this specific probiotic strain was resolved by Finnish surveillance data over the decade from 1990 to 20006.

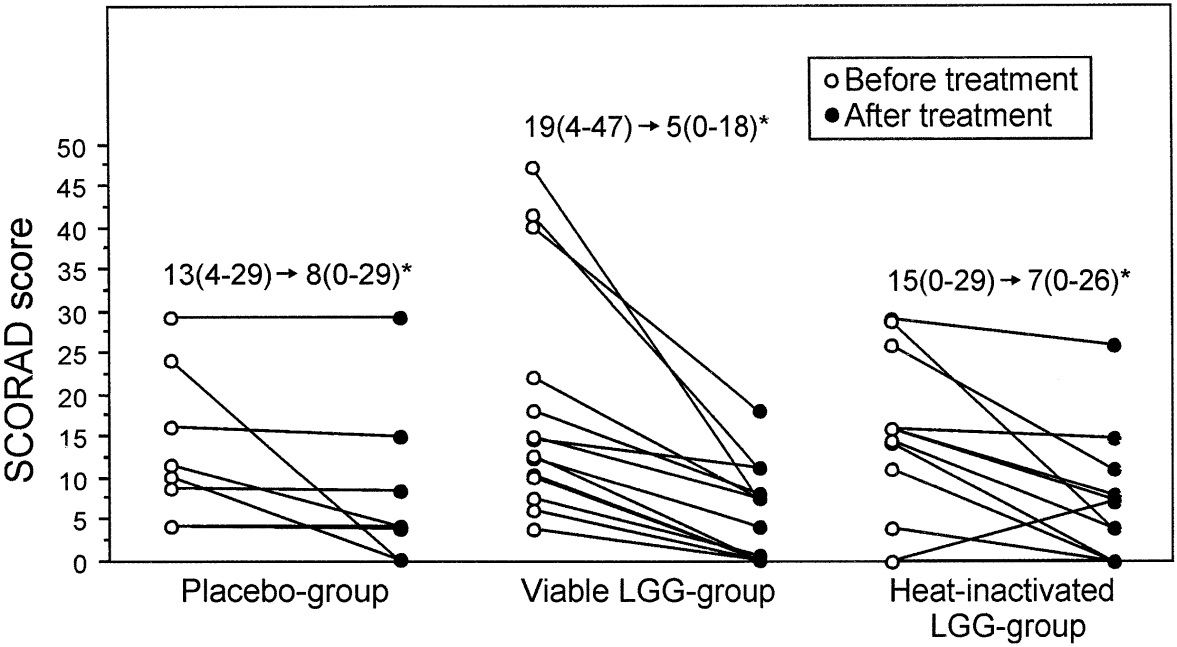

There are hundreds of studies that support LGG being clinically effective. Many researchers set up LGG-treated groups and placebo-controlled groups to check to see if symptoms had been significantly improved, and numerous clinical trials had confirmed its incidence of diarrhea, atopic eczema, and respiratory infections. Much more efficacy of LGG such as the regulation of the immune responses and obesity prevention is being reported continuously7–14.

The genome of LGG strain was also investigated to reveal its genetic properties. Kankainena et al., 2009 found that LGG has 143 unique proteins compared to other strains, of which 24 proteins were related to carbohydrate transport and metabolism. It is reported that these unique proteins allow LGG to utilize monosaccharides and disaccharides as a substrate for metabolic activities in the small intestine rich in carbohydrates. These features might help LGG strains colonize the small intestine readily. The author also found that mucous membrane properties of LGG were due to protein-mediated strain-specific ability through the previous studies about LGG to adhere to intestines is thought to be sensitive to protease. Furthermore, this study has shown amazing results that spaC has an essential role in the interaction of LGG strains with mucous membranes and explains its ability to persist in the human intestinal.

LGG has unique characteristics and strengths compared to other probiotics, and its effect on health improvement has been proven clinically. As existing technologies are continuously being updated and new technologies are being invented to use on a huge commercial scale, we hope more LGG-like probiotics will soon be isolated, characterized and refined to use in the prevention and treatment of other significant diseases.

References

- 1.Silva M, Jacobus NV, Deneke C, Gorbach SL. Antimicrobial substance from a human Lactobacillus strain. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. August 1987:1231-1233. doi:10.1128/aac.31.8.1231

- 2.Kankainen M, Paulin L, Tynkkynen S, et al. Comparative genomic analysis of Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG reveals pili containing a human- mucus binding protein. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. September 2009:17193-17198. doi:10.1073/pnas.0908876106

- 3.Corcoran BM, Stanton C, Fitzgerald GF, Ross RP. Survival of Probiotic Lactobacilli in Acidic Environments Is Enhanced in the Presence of Metabolizable Sugars. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. June 2005:3060-3067. doi:10.1128/aem.71.6.3060-3067.2005

- 4.Gregor R. The Scientific Basis for Probiotic Strains ofLactobacillus. American Society for Microbiology. https://aem.asm.org/content/65/9/3763/article-info. Published 1999.

- 5.Reid G, Burton J. Use of Lactobacillus to prevent infection by pathogenic bacteria. Microbes and Infection. March 2002:319-324. doi:10.1016/s1286-4579(02)01544-7

- 6.Salminen MK, Tynkkynen S, Rautelin H, et al. LactobacillusBacteremia during a Rapid Increase in Probiotic Use ofLactobacillus rhamnosusGG in Finland. CLIN INFECT DIS. November 2002:1155-1160. doi:10.1086/342912

- 7.Vanderhoof JA, Whitney DB, Antonson DL, Hanner TL, Lupo JV, Young RJ. Lactobacillus GG in the prevention of antibiotic-associated diarrhea in children. The Journal of Pediatrics. November 1999:564-568. doi:10.1016/s0022-3476(99)70053-3

- 8.Szajewska H, Kotowska M, Mrukowicz JZ, Arma′nska M, Mikolajczyk W. Efficacy of Lactobacillus GG in prevention of nosocomial diarrhea in infants. The Journal of Pediatrics. March 2001:361-365. doi:10.1067/mpd.2001.111321

- 9.Nixon AF, Cunningham SJ, Cohen HW, Crain EF. The Effect of Lactobacillus GG on Acute Diarrheal Illness in the Pediatric Emergency Department. Pediatric Emergency Care. October 2012:1048-1051. doi:10.1097/pec.0b013e31826cad9f

- 10.Lee J, Seto D, Bielory L. Meta-analysis of clinical trials of probiotics for prevention and treatment of pediatric atopic dermatitis. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. January 2008:116-121.e11. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2007.10.043

- 11.Kirjavainen PV, Salminen SJ, Isolauri E. Probiotic Bacteria in the Management of Atopic Disease: Underscoring the Importance of Viability. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition. February 2003:223-227. doi:10.1097/00005176-200302000-00012

- 12.Hojsak I, Abdovic S, Szajewska H, Milosevic M, Krznaric Z, Kolacek S. Lactobacillus GG in the Prevention of Nosocomial Gastrointestinal and Respiratory Tract Infections. PEDIATRICS. April 2010:e1171-e1177. doi:10.1542/peds.2009-2568

- 13.Kekkonen RA, Vasankari TJ, Vuorimaa T, Haahtela T, Julkunen I, Korpela R. The Effect of Probiotics on Respiratory Infections and Gastrointestinal Symptoms during Training in Marathon Runners. International Journal of Sport Nutrition and Exercise Metabolism. August 2007:352-363. doi:10.1123/ijsnem.17.4.352

- 14.Luoto R, Kalliomäki M, Laitinen K, Isolauri E. The impact of perinatal probiotic intervention on the development of overweight and obesity: follow-up study from birth to 10 years. Int J Obes. March 2010:1531-1537. doi:10.1038/ijo.2010.50